What Is a Sensor? An In-Depth Look at Devices and Their Types

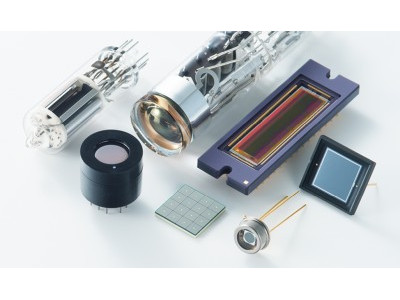

A sensor is an electronic or electromechanical device designed to convert a particular external influence into an electrical signal. That’s one of the simplest and most practical definitions you’ll find. You can imagine a sensor as a “black box”: it accepts some form of input-be it pressure, temperature, motion, or light-and outputs a signal suitable for transmission and processing in automation, security, or control systems.

Below, we’ll explore how sensors work, the various types available in the USA, and how you can leverage them for countless applications. If you want to learn more about different brands, real-world testing, or even code compliance, visit safsale.com, where we share resources and insights tailored to American markets and regulations.

1. Device Basics and Working Principle

From a high-level perspective, sensors can be categorized by the nature of what they detect. Here are two broad groups based on input:

Contact Sensors

- Rely on mechanical interaction with the target.

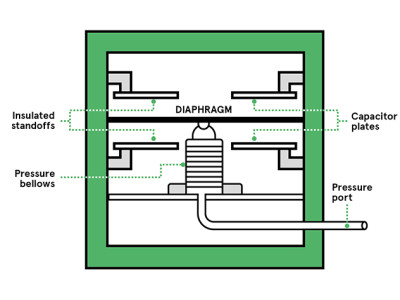

- Typical examples: limit switches, flow sensors for fluids or gases, pressure sensors that physically deform under load.

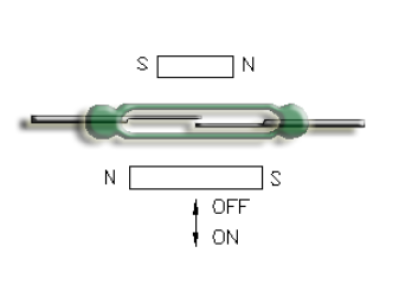

Non-Contact Sensors

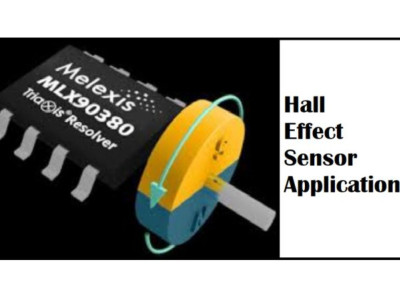

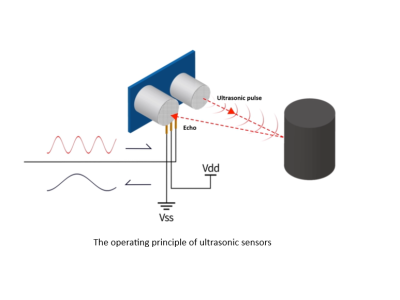

- Detect changes via magnetic, optical, microwave, capacitive, inductive, or ultrasonic principles-without direct mechanical contact.

- Each principle has unique benefits. For instance, inductive sensors only respond to ferrous metals, while optical or microwave sensors can operate over significant distances.

1.1 Why Sensor Type Matters

- Inductive Sensors: Great for metal detection but won’t sense plastics or wood.

- Ultrasonic and Microwave: Effective for long-range detection, like in large warehouses or outdoor US-based applications.

- Optical (Photoelectric): Ideal for detecting interruptions (like counting items on a conveyor).

- Magnetic: Often used for door or window security systems, responding to the presence or absence of a magnet.

Because each technology has a specific detection method, you’ll choose a sensor type based on range requirements, object material, environmental conditions, and precision.

2. Where Are Sensors Used?

Sensors are integral to security and fire alarm systems, industrial automation, telemetry, and real-time control processes. For example:

- Detection of Objects: Determining if an item is within a certain zone.

- Measurement of Position or Speed: Tracking a component’s movement, direction, or speed on an assembly line.

- Environmental Monitoring: Checking temperature, composition, or humidity in climate control or greenhouse setups.

One everyday US usage scenario is a smoke detector in fire alarm systems-detecting early combustion stages by sensing particulates or changes in air composition. Another example is a level sensor for liquids or granular materials in factories or municipal water treatment plants.

3. Types of Output Signals

Just as sensors vary in the quantity they measure, they also produce different output signals. Understanding these is vital for selecting the right sensor in your system design.

3.1 Threshold (On/Off) Output

Threshold or switching sensors provide only two states: “0” (off) or “1” (on). They act like an electronic switch:

- Dry Contacts: The sensor’s output is purely mechanical, like a relay contact that can handle a specific voltage/current range.

- Solid-State Switches: Using transistors, thyristors, or triacs to create the on/off effect electronically.

Key Parameter: The maximum or nominal current and voltage the sensor can switch. Some sensors handle a brief surge at a maximum rating, while others allow continuous duty at a nominal rating.

Benefit: Universality-you can interface the on/off signal with nearly any control system or PLC, making these sensors popular in simpler or direct-control US-based setups.

3.2 Analog Output

An analog sensor produces a signal-often a voltage or a current (4-20 mA is typical in industrial applications)-that proportionally tracks the measured parameter. Examples:

- Temperature Sensor: The output voltage changes with temperature.

- Pressure Transducer: Voltage or current increases with growing pressure.

Because analog signals are continuous, they’re especially informative. However, they need specialized processing hardware, like analog-to-digital converters or dedicated input modules in a PLC.

3.3 Digital (Binary or Serial) Output

Digital sensors can transmit data in a purely binary or serial protocol format. They:

- Use logic levels (like 3.3 V or 5 V) or digital pulses to communicate measured values and possibly a device address or additional status data.

- Often appear in advanced systems that incorporate microcontrollers, requiring compatible input modules.

This approach can carry rich data (temperature, humidity, ID codes, etc.) over a single bus line, but the sensor and receiver must speak the same digital protocol (e.g., I²C, SPI, 1-Wire).

4. Examples and Application Notes

Here are some sensor categories commonly seen in USA environments:

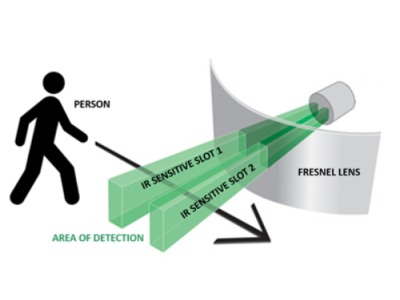

- Motion Detectors (Optical or Microwave)

- Popular in security lighting or automatic doors.

- Smoke or CO Detectors

- Fire safety in residential and commercial buildings, triggering alarms or sprinklers.

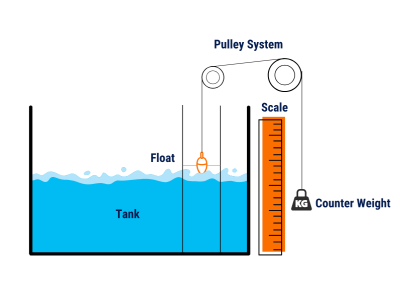

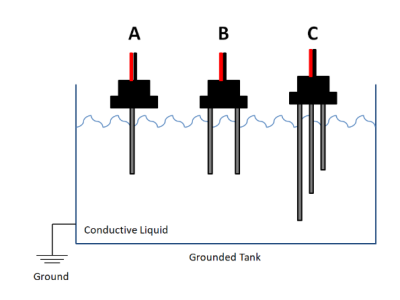

- Level Sensors

- Monitor liquid or powder levels in industrial tanks, farm silos, or municipal water towers.

- Temperature Sensors (Thermistors, Thermocouples, RTDs)

- HVAC systems, industrial process lines, home appliances.

- Gas Sensors

- Checking for gas leaks (propane, natural gas), or indoor air quality (like CO₂).

When choosing a sensor, pay attention to minimum object size detection, distance range, environment (dust, moisture, temperature extremes), and maintenance considerations (like cleaning or recalibration).

5. Practical Output Signal Considerations

- Power Requirements: Some sensors need a stable 12 V or 24 V DC supply (often standard in US-based industrial control). Others might run on 5 V or even 3.3 V if integrated into microcontroller boards.

- Signal Conditioning: For analog signals, you might need buffering, filtering, or amplification. For digital sensors, watch out for bus speeds and cable lengths.

- Isolation: If you’re dealing with hazardous or high-voltage areas, ensure the sensor provides electrical isolation or that you add optocouplers as needed.

6. Construction and Environmental Ratings

Sensors in automation and control must often function reliably in dusty, wet, or hot conditions. Pay close attention to:

- IP Rating: Indicates dust and water resistance (e.g., IP65, IP67).

- Temperature Range: Minimum and maximum operating temperatures.

- Mounting Style: Threaded housings, flanges, or flush mount options.

The exact sensor design depends on the application. For example, a photoelectric sensor in a US packaging plant might need a lens cleaning solution if dust accumulates on the sensor’s face.

Conclusion

A sensor is fundamental to detecting and converting real-world phenomena into electrical signals, bridging physical events to digital or analog control systems. Whether it’s a simple contact switch for mechanical movement or a sophisticated ultrasonic device measuring distances, sensors play a pivotal role in modern automation, security, and monitoring systems.

When selecting a sensor:

- Determine the target parameter (e.g., temperature, motion, level).

- Choose contact vs. non-contact based on materials and environment.

- Evaluate the output signal (threshold, analog, or digital) for integration into your existing control system.

- Check environmental and electrical specs (voltage, current, IP rating, and temperature).

For more guidance on selecting or installing sensors in the USA, including brand recommendations and code compliance tips, visit safsale.com. By understanding your requirements and the sensor’s capabilities, you’ll achieve a reliable, efficient solution-whether you’re managing a home security setup, industrial production line, or a complex building automation network.