Hall Effect Sensor: How It Works, Types, and How to Check It

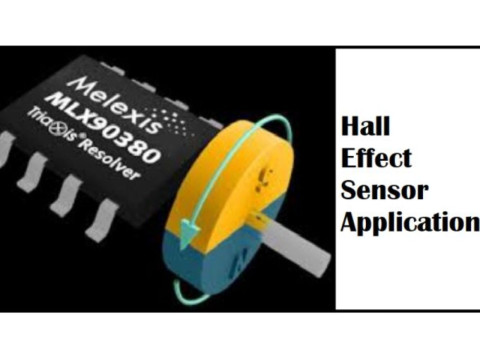

The Hall effect sensor is a device that converts a magnetic field’s strength or presence into an electrical output signal. Originating from the Hall effect—the force on charged particles in a conductor crossing a magnetic field—the sensor’s core element is typically a semiconductor that produces a small voltage when exposed to a magnetic field. Modern circuits amplify that voltage to create a precise, stable output.

Hall sensors are everywhere: from automotive ignition systems and motor controllers to laptop lid sensors and current measuring modules. Here, we’ll look at how these sensors are used, especially in vehicle applications, outline their main types (analog vs. digital), and show some simple ways to test one. For a more in-depth US-focused approach—like recommended brands or automotive wiring guidelines—visit safsale.com, where we provide practical references on Hall sensor integration.

1. Operating Principle of a Hall Sensor

Hall effect: When a conductor or semiconductor plate carrying current is placed perpendicularly to a magnetic field, the electrons moving through it are deflected by the Lorentz force. This deflection creates a small potential difference across the plate’s other sides:

Although voltage from the bare effect might be just tens of millivolts, modern Hall sensors feature semiconductor processing and integrated amplification circuits, enabling them to switch signals up to standard logic levels.

Why Automakers Use It

In a car engine, timing is crucial: a Hall sensor can sense the rotation of the crankshaft (or camshaft), converting the magnet’s position into a reliable, fast digital signal. This triggers the spark exactly when needed, improving performance and fuel economy compared to older contact-based breakers.

2. Hall Sensor Types

2.1 Analog (Linear) Hall Sensors

- Output is a voltage proportional to the magnetic field strength (could be biphasic or unipolar).

- Often used for current sensing modules, contactless joystick position sensors, or measuring magnetic flux in industrial applications.

2.2 Digital (Switch) Hall Sensors

- Provide a binary on/off signal when the magnetic field passes a certain threshold.

- Unipolar: Activates with one polarity (like a north pole approaching) and deactivates when it leaves.

- Bipolar: Switches “on” with a specific pole, then “off” with the opposite pole.

- Common in vehicle ignition distributors, speed sensors, or any place you want a clean digital pulse as magnets rotate or pass.

Automotive Example

In many ignition systems, a disk/rotor with teeth or vanes passes between a tiny permanent magnet and the Hall element. Each tooth blocks or distorts the magnetic flux, toggling the sensor’s output. The sensor outputs a stable high/low signal to the ECU or ignition module—no “bouncing” contacts or mechanical wear.

3. Practical Applications in the USA

- Automotive Crankshaft Position

- Precisely times spark or injection events.

- Replaces older mechanical distributors.

- Contactless Current Measurement

- High power lines in solar inverters, EV chargers, or DC power supplies.

- Laptop Lid Sensors

- Detects when a magnet in the screen assembly closes, prompting sleep mode or power saving.

- Brushless DC Motors

- Hall sensors track rotor position for smoother commutation.

4. Checking/Testing a Hall Sensor

Sometimes a Hall sensor fails, leading to:

- Hard starting or no start

- Engine stalling or unpredictable RPM fluctuations

Quick ways to test:

Swap with a Known-Good Sensor

- If spares are cheap, swapping is the easiest. If the problem goes away, the old sensor was at fault.

Use a Voltmeter

- Keep the sensor connected to vehicle power (or a lab supply).

- Place one meter lead on the sensor’s ground wire, the other on the signal wire.

- When you insert a piece of ferrous metal or magnet, watch the output:

- For a typical automotive sensor:

- No vane blocking = ~ 0.4 V (or “low” state)

- Vane or magnet present = ~ 11 V (near battery voltage, “high” state)

- For a typical automotive sensor:

- This can differ depending on the sensor’s polarity or type, but you should see the output toggling between near supply voltage and near zero as you move a piece of steel or the rotor tooth in/out of the sensor’s magnetic field.

Advanced or specialized testing (like using an oscilloscope for dynamic signals) is generally left to professional automotive techs.

5. Design Strengths and Weaknesses

Strengths

- No Mechanical Contacts: Minimal wear, stable timing.

- High Switching Speed: Ideal for high-RPM engines.

- Compact & Low Cost: The integrated chip is small and widely manufactured.

- Reliability: Good in harsh environments when shielded properly.

Weaknesses

- Sensitive to EMI (electromagnetic interference), requiring shielding or robust electronics.

- Slightly less robust than purely mechanical contacts if the supporting electronics fail.

- Output typically requires a stable power supply and pull-up or open-collector wiring arrangement.

6. Conclusion

A Hall effect sensor is a non-contact device that transforms magnetic field interactions into an electrical output. In automotive contexts—especially ignition and engine management—it replaces older mechanical distributors, delivering consistent timing and enhanced reliability. Outside of cars, it’s found wherever magnetic detection or contactless measurement is crucial, from appliances and laptops to high-power current sensing.

Key Points:

- Analog (proportional) vs. Digital (on/off) sensor types.

- Typically uses a permanent magnet and a rotating ferrous vane or gear in automotive.

- A simple voltmeter check can confirm if it toggles from near 0 V to near supply voltage.

- Swapping the sensor with a known-good unit is often the fastest troubleshooting method.

For deeper dives—like brand suggestions, electrical schematics, or advanced testing under US conditions—see safsale.com. With a properly functioning Hall effect sensor, your engine ignition or other control systems will operate with precision and reliability.