Liquid Level Sensors: Types, Selection, and Practical Uses

Devices that monitor the level of water or other liquids come in many forms, each with its own operating principle. By choosing the correct sensor for your application—be it industrial, commercial, or residential—you can streamline processes, enhance safety, and reduce costs. In the USA, these sensors find use in everything from wells and pumps to industrial tanks and smart home systems.

Below, we’ll explore the main liquid level sensor types, how they measure or signal fluid levels, and where each thrives. If you’re seeking more in-depth guidance—like brand options, wiring specifics, or local code considerations—check safsale.com for American-focused resources.

1. Why Liquid Level Sensors Matter

Level sensors fall into two broad categories:

- Level Transmitters (Continuous Measurement) – Provide ongoing or “analog” (or digital) readouts, often for remote monitoring or automated control.

- Level Switches / Limit Switches (Discrete Signal) – Trigger an alert or switch circuit when fluid hits a preset level.

Modern sensors can supply data for:

- Real-time water level tracking

- Alarms for low or high thresholds

- Volume estimates in oddly shaped tanks

- Data logging and advanced process control

2. Contact vs. Non-Contact Sensors

2.1 Contact Sensors

- Mounted such that they physically contact the liquid.

- Examples: Float sensors, conductive (conductometric) sensors, capacitance probes, vibrating forks.

2.2 Non-Contact Sensors

- Ultrasonic or radar waves measure levels from above.

- No direct contact with fluid—handy for harsh or corrosive liquids.

- Typically more expensive but also more versatile, especially for unusual or hazardous media.

3. Major Sensor Types and Their Advantages/Drawbacks

Radar (Microwave) Level Sensors

- Non-contact, use microwave pulses or FMCW (frequency modulated continuous wave) to gauge distance to fluid.

- Work across broad temperature/pressure extremes, unaffected by foam or vapor.

- Pros: Very accurate, minimal media contact.

- Cons: Often pricey, require skillful setup.

Ultrasonic

- Non-contact, send high-frequency sound pulses and measure return time from liquid surface.

- Best for water and similar liquids. Generally cost-effective, easy to maintain.

- Limitations: Foaming or turbulence can disrupt readings. Sensitive to wind or heavy vapors.

Capacitance & Conductive (Conductometric)

- Typically have an electrode or probe that changes in capacitance or conductivity when in contact with liquid.

- Great for water, beverages, or solutions—conductive sensors specifically need liquids that conduct electricity.

- Pros: Simple, reliable. Electrode length is easily adjusted.

- Cons: May require calibration for changes in fluid properties.

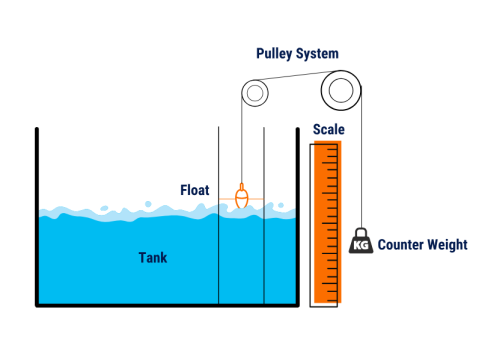

Float Sensors (Mechanical or Magnetic)

- A float rises/falls with fluid, flipping a switch or magnet-based reed sensor.

- Pros: Low cost, straightforward.

- Cons: Only detect discrete positions. Not suited for sticky or foamy media. Mechanical parts can jam or wear.

Hydrostatic (Pressure-Based)

- Measure hydrostatic pressure at a known depth. Pressure correlates to fluid level if density is constant.

- Common for well water measurement, irrigation controls.

- Caution: Changing fluid density or external pressure can skew results.

Optical Sensors

- Detect changes in light reflection/refraction when the sensor tip contacts liquid vs. air.

- Great for pressurized or vibratory conditions where float or reed sensors might fail.

- Typically more expensive and sensitive to clarity/opacity of fluids.

Vibratory (Tuning Fork) Level Switches

- A vibrating “fork” changes amplitude/frequency when immersed.

- Works on thick, foamy, or sludgy media.

- Not for precise continuous measurement—mostly used as an on/off switch at a specific level.

4. Where These Sensors Excel

- Water & Similar Liquids: Ultrasonic, float, vibe switches, capacitive, or hydrostatic.

- Acidic or Corrosive Solutions: Capacitance or vibratory sensor with properly coated or non-contact radar.

- Foamy or Sticky Media: Typically capacitive (radio-frequency) or vibratory.

- High Viscosity: Vibratory, non-contact radar, or robust ultrasonic.

Take note of the tank’s shape, material, and fluid temperature or pressure. Some sensors require direct tank wall insertion (“wetted” design), which may not be feasible with certain chemicals or pressurized vessels.

5. Selecting the Right Sensor for the USA

When choosing a sensor:

- Fluid Properties

- Conductivity, viscosity, presence of foam or vapor.

- Tank Design

- Volume, shape, top/bottom access, material (metal, plastic).

- Measurement Goal

- Continuous reading vs. just a limit switch.

- Installation & Service

- Can you easily mount a sensor from above? Is cutting into tank walls permitted? Are cleanliness or CIP (clean-in-place) considerations needed?

- Integration

- Will the sensor feed a PLC, microcontroller, or a simple on/off relay?

- Is an analog (4–20 mA) or digital (Modbus, I²C) output needed?

For home use—like controlling a well pump—basic float or conductometric sensors often suffice. Hydrostatic sensors are popular for well depth monitoring. For industrial or municipal systems, you might choose ultrasonic or radar to get precise continuous data over large ranges.

6. Typical Use Cases

- Residential Wells and Sumps

- Float switch or hydrostatic sensor ensures pumps don’t run dry.

- Pools or Ponds

- Float sensors or ultrasonic to keep track of water level.

- Industrial Tanks

- Radar or ultrasonic for full-range reading; capacitive or vibronic for overfill prevention.

- Food & Beverage

- Capacitive or optical sensors for sanitary surfaces, possibly CIP-rated.

- Corrosive Chemicals

- Non-contact radar or special coated electrode sensors to withstand harsh liquids.

7. Cost and Maintenance Considerations

- Float or Conductive solutions are typically budget-friendly and easy to install.

- Ultrasonic and vibratory are medium-range cost, requiring stable mounting but relatively low maintenance.

- Radar systems can be premium priced but deliver top performance in challenging conditions.

- Sensor Cleaning or calibration might be needed if the fluid leaves residues or if environmental factors (like foam) vary drastically.

Conclusion

Selecting a liquid level sensor boils down to understanding the fluid’s properties, the tank environment, and the level data you need—be it a simple on/off alarm or detailed continuous monitoring. Whether you rely on float switches, capacitive electrodes, ultrasonic pulses, or advanced radar systems, each approach excels in different scenarios.

Key Takeaways:

- Contact vs. Non-Contact: Contact sensors are more common and cost-effective. Non-contact solutions (ultrasonic, radar) suit harsh or sensitive processes.

- Single-Level vs. Continuous: If you only need high or low level signals, a switch-based device suffices. For advanced monitoring, pick a transmitter (ultrasonic, radar, or capacitive).

- Consider the Fluid: Viscosity, foam, or stickiness can hamper some sensors.

- Check Installation: Does your tank allow top-entry? Are the walls metal or plastic? Is cutting or drilling feasible?

For more specialized recommendations—like which brand to pick for acid solutions or code-compliant wiring in the USA—head over to safsale.com. With the right sensor in place, you’ll track fluid levels accurately, automate your pumps or valves seamlessly, and maintain a safe, efficient process or environment.